The Mindvalley quest Becoming Focused and Indistractable has been marketed heavily on social media. Maybe many of you were led here by the video in which Vishen Lakhiani invites you to take a look at his Google time block calendar that looks like a rainbow exploded on it (see below. It was intentionally blurry in the video – apparently the details of his schedule are private!):

In the marketing video for this course, Lakhiani suggests himself as a paragon of what the quest can give to you: ”Most people look at that calendar and think that I’m crazy busy. I’m actually not—I’m crazy optimized!”

Obnoxious.

But also shamelessly ambitious and confident. It worked. I clicked to watch a sneak peek of this quest right away.

The sneak peek was cool – a pleasant, productivity-themed discussion between Vishen Lakhiani and Nir Eyal, the creator of the quest. In the video, what convinced me to take it was not Vishen Lakhiani’s repeated promise of becoming a crazy optimized superhuman, but Nir Eyal’s down-to-earth reiteration of the core selling point: the gist is not to abandon your social media and become a machine, but to learn to master your life so that you don’t need to restrict yourself anymore. Instead, you’ll learn ways of thinking, ways of organizing your environment, and ways of making decisions that make it desirable to postpone temptations for greater goals, make it automatic to divide the hours in your days according to your values, and thus make it possible to fill your days with what makes you happy, not just what they end up being filled with after reacting to external needs throughout the day. I love that, and I gave the quest a chance.

So, this review is about that chance – 8 weeks of my life that I devoted to becoming indistractable. If you’re also thinking of taking the quest, in this review, you’ll find a comprehensive description of the themes of the quest, an interpretation of how its goals relate to the tasks performed in it, and the value that I found and didn’t find in it, in my particular life-situation (if you want to compare it to yours, see bio at the bottom).

Table of Contents

The resources you're given

The 27 lessons take no more than 3 hours to watch, making an average video about 6 minutes long. In practice, the videos vary from 2 minutes to 16 minutes. While one lesson will take no more than a few minutes to watch, the time it takes for you to get the benefit out of it is of quest is, of course, more. In fact, the quest covers your whole life:

“You” things include the things that you need to function well. It can be sleep, food, hobbies, alone-time, it can be Netflix and chill, it can be your dream of writing a novel. “Relationship” things are your relationships with your family, friends, lover, children, or any other social bond you have. “Work” is your payroll, your side hustle, and your hobby (if it is work more than a leisure activity).

The quest proceeds from one module to another, and you will get one video per day for 27 days. There is no need or request to complete the course in 27 consecutive days, and nothing stops you from spending either less or more time in total on the quest. Mindvalley provides the option of choosing to do the quest on a plan where the videos unlock in a set order or doing the quest on your own schedule and unlocking them all right away. I chose to unlock all of them right away, and experiment with its techniques one theme, rather than one video, at a time.

The quest comes with a supplemental workbook. It’s a simple pdf file that you can download from the quest page (obviously at no extra charge), but it works really well; its layout is clear and beautiful, and it really helps to concretely understand what the lessons suggest you try out.

If you want to go all out, I recommend also using an actual journal to keep track of your progress on this quest. The workbook in and of itself is great, and I heartily recommend using at least that, but the videos also raise other questions than the exercises given in this book, and it might be useful to write them down in your journal and reflect on them later on.

Initial review: What the quest promises and my starting point

You’re asked to fill in an 8-point survey on the first and the last day to have a concrete point of comparison. The survey has nice, color-coded responses to how well the statements correspond to your situation:

The survey claimed, and I answered the following on the first day of the course:

1. My schedule reflects my values, aspirations, and goals. I rarely go off track

Neither agree nor disagree (3). I do go off track, even if my schedule reflects my values, aspirations, and goals. There are just too many of them to fit in one day.

2. I can stay focused on achieving my goals and living a purposeful life. I am fully in control of how I spend my time.

Disagree (1). While I have achieved many of my goals and consider my life purposeful, I do feel like it often happens rather by accident than by plan – at least not by my plan.

3. I know how to master cues in an external environment that lead me to distraction.

Strongly disagree (0). I’m not sure what this means, but if it means what other people ask of me, I am sometimes too eager to please other people or to use them as an excuse to escape my own responsibilities.

4. I know how to use my e-mail, group chats, desktop, smartphone in a way that stimulates my efficiency and productivity.

Disagree (1). I am not sure what it would mean to make them work for my productivity. Apart from the smartphone, nothing really creates a major distraction temptation for me.

5. I’m fully present in the now absolute majority of the time.

Strongly disagree (0). I definitely live in the future.

6. I easily avoid being distracted by technology.

Disagree (1). I feel the need to check my phone often, and I find myself scrolling for 60 minutes after stopping to check one thing.

7. I am deeply aware of my internal triggers, the root causes of my distractions, and I know how to navigate them.

Disagree (1). I am not aware of these, and this sounds alarmingly psychoanalytical.

8. I have strong routines that help improve my productivity.

Somewhat agree (4). I have read the modern classics of the productivity hype and have my atomic habits in place, yet the days often escape me.

So, that’s my starting point. The quest doesn’t ask you to give a grade, but I find it instructive: on the scale of answers, I give points 0—6 from the lowest (strongly disagree) to the highest (strongly agree). On this scale, then, I got 11 points when the full points would have been 48 points (8 x strongly agree i.e. 6 points). Yeah. I’ll return to this at the end of the review!

Before delving into the days of the quest, I’ll share a few words on its host.

Nir Eyal as the guide of this quest

One of the aspects that makes this quest very relatable is Eyal’s openness about his own flaws and struggles. He loves sweets (proof in picture below, haha), social media, and Netflix binges with ice cream, and he used to engage with them on a daily basis. He used to be out of shape, addicted to social media, and struggled to pay attention to his family.

Upon realizing that these were problematic habits – a step that already had taken its time – he tried to restrict himself with various techniques that make it impossible to engage in harmful activity, like using a simple 1990s phone instead of a smartphone, buying an old word processor without internet connection, etc., to thus force himself to be focused. Yet these just shifted the problem to other distractions; suddenly, chores were super enticing, and reading a book seemed like a valuable alternative to writing. We’ve all been there.

After chronically failing, Eyal developed and used the methods that he teaches in this quest. He achieved positive changes: he gained muscle, improved his productivity, increased the happiness of his family, and found enjoyment in having control over his own life. And then, it is the quest-taker’s turn to do the same in their context. Let’s see how I fared.

Module I (days 1-5): Phenomenon and importance

The first module explains what happens in us – inside us – when we get distracted and why it’s important to intervene in that process. The problem of distraction, Eyal explains, is timeless and thus runs deeper than the temptations provided by our smartphones. The same blame that we now place on smartphones was placed on arcade games and black-and-white television back in the day – and the problem of distraction was acknowledged already in texts by ancient philosophers. Thus, distraction has always been around (and always will be), even if finding reasons to get distracted is easier now than ever (and will, most likely, be even easier in the future).

Eyal’s way of explaining the problem is simple: we get distracted because we want to avoid pain and discomfort. This claim is exemplified by brief stories ranging delightfully from folk beliefs to his previous coworker’s relationship with her pedometer to fresh-water snails and a myriad of psychological case studies.

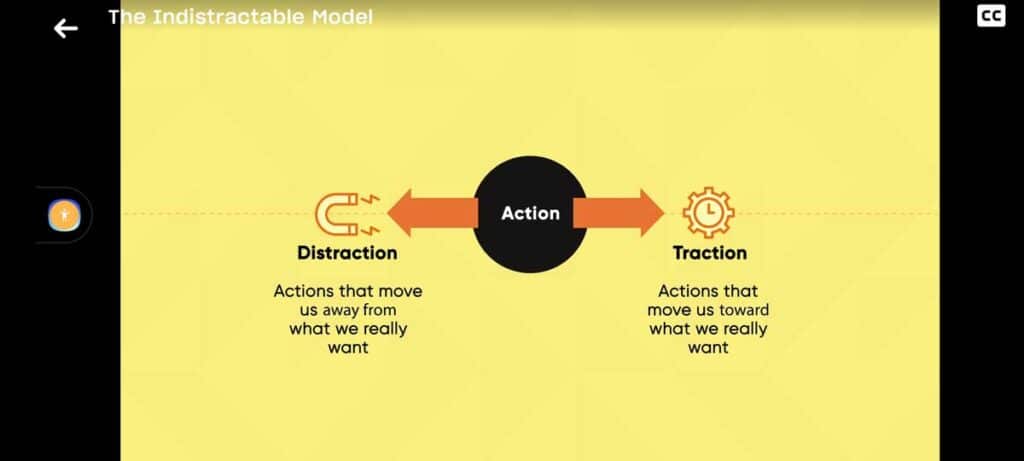

The wish to avoid discomfort is not presented as an accusation or something to get rid of. It’s just the way it is, given the structure of our brain. Understanding the natural mechanism that distraction = avoiding discomfort makes it possible to intervene in the action that allows us to avoid discomfort:

But the first five days are about understand your motivations related to the distractions and the traction they distract you from – not yet the actual actions that intervene between traction and distraction. You need to sit with your situation and evaluate, really, whether you actually want to take a step towards doing things differently from how you’ve used to.

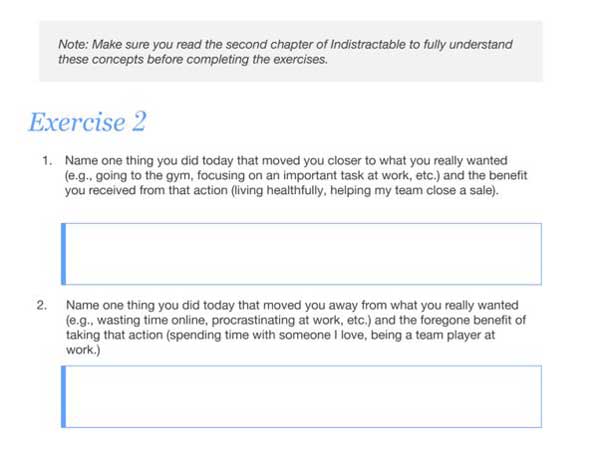

The workbook gives you exercises, much like journaling prompts but shorter, through which to think about your relationship with being distracted. The exercise book and the videos work together in that the exercise book asks you to reflect back on the contents of the video, ideally with some time in between watching the video and sitting with the workbook. You can schedule these activities the way you want.

My schedule was such that I would watch the video on my lunch break and fill the workbook in at the end of the day. I guess you’d benefit the most from watching the video early in the morning to have the maximum amount of time to let it stir, but I chose to rather meditate in the morning (using this technique, by the way), and it felt excessive to do both.

I’ll make an example of the above Exercise 2 (as it’s a PDF, the boxes do not expand as you write, so it might be nice to actually print the workbook out and use a pen). The video of the day had given examples of life goals and health benefits that people let slip, not because something huge, good or bad, does or doesn’t happen, but because they, day to day, neglect taking the initiative and keep making the same decisions that keep them were they are.

Guided by the video, I made it a thing to stop in the middle of the day at some point and reflect on what I was doing and in which of the slots this action would fall. Some examples of how I fared: I did meditation and yoga in the morning, but I scrolled through Instagram on my commute instead of reading or listening to a podcast as I had planned. I had protein porridge (yum!) for breakfast but skipped lunch and thus couldn’t fight the urge to down a huge chocolate bar before dinner. I was productive at my 9-to-5 and worked on an essay related to my studies on pedagogy but didn’t work on my Ph.D. thesis at all. I did have a lot of cool time with my daughter taking her to practice, but coming home, I found it too late to have a Yu-Gi-Oh match with my son even though I’d said on the previous day that we could play.

As the one thing distilled from these sporadic notions, I wrote down:

I went to the gym in the morning and thus am doing well at staying healthy and getting fit.

I went to the gym instead of working on my doctoral thesis and thus didn’t make progress toward obtaining the degree.

During this day, I realized that my distractibility is largely related to just having too many things to do. I believe this resonates with many people, as many people work with demanding combinations like children and work or a serious hobby and studies or sick relatives to take care of and your own life to run on the side or demanding pets, work, and a new relationship, for example. My goal in this quest is, in fact, not to get rid of bad habits but to find ways to manage the constant shame of feeling that I didn’t spend my time right. (Believe me, it goes beyond balancing the gym and academia.)

There are different modes of being distracted, and the doom-scrolling zombie is just one of them. You’re also distracted when you’re very busy and reacting to the endless information flow on your email all the time instead of devoting time to focused work. You’re also distracted if you haven’t set down the things you should be doing that day and instead go with what everyone else needs from you. You’re also distracted when you’ve put off a bigger life goal because you just don’t have the time. This is the phenomenon covered in module I. You can be only one of these types or you can be all of these at once. Yet the same tools (introduced in modules 2-5) can be made to work on all, as all distraction comes down to avoiding some kind of pain.

Module II (days 6-8): Internal triggers

The next three days teach you how to master the impulse to alleviate the pain of discomfort. Citing extensive research on psychological tests implemented on human and animal subjects alike, as well as drawing from the teachings of the Stoic philosopher Hierocles, and citing the philosophical literary figures Goethe and Dostoyevsky, Eyal explains the “Ironic Process Theory”: the phenomenon that we fully abstain from something and end up making it all the more attractive (anyone who saw the Twilight Series in their teens will understand immediately). Unfortunately, if something becomes more attractive, it also becomes more rewarding “and thus more habit-forming” as Eyal points out. Therefore, abstinence is not the way to mastery.

Eyal gives you tools with which to reimagine the task. Instead of denying anything right away, you can approach it as something that you don’t engage in right now. Eyal offers a structured process to do this, and three specific techniques. Instead of going through the minutiae of it (I think it’s best experienced in the quest if you so choose – and you’re anyway probably here to get an idea about the content rather than to learn per se), I merge these aspects into a step-by-step simplification of them:

- You acknowledge the discomfort but do not act on it yet. You simply stop for a bit.

- You give the discomfort a name and really try to understand why it pops up.

- After sitting with it for a while, see if you still feel like you absolutely need to react to it. If not, proceed with what you were doing before the discomfort appeared. If yes, say to yourself that you can do it after a certain amount of time, and if the urge is still there after that time, you allocate time for it.

- Is this a liminal moment, such as standing at the traffic lights or waiting for something to start? Those situations are the easiest for time-thieves, so in those situations the window for distraction might pass already by just sitting with it for a bit—the changing traffic lights, someone appearing in the room or similar will distract you from your distraction again.

You can also try making it into a game. Productivity literature has many versions of this approach; you could reframe it as a sequence, like a round of actions, and try to top your time each round, for example. However, Eyal’s technique is a little different, more fundamental if you wish. Borrowing the original idea from Ian Bogost, he explains that you should learn more about what it is you’re getting distracted from. This works especially with mundane, boring, or daunting tasks that are a bore but that you should commit to doing consistently. Learning more about the technical finesse of cleaning or gardening, for example, can make it inherently more exciting, as we are drawn to what we can do well. Learning more about a mundane task adds deliberateness and novelty to it.

Eyal gives an example of a guy who learned literally about grass (!), about it growing, to make his lawn-mowing into an art he learned to enjoy. Eyal guides you to play absurdly keen attention to detail, to learn ridiculously much about this task, and in that way make it more interesting.

This approach, I think, works only with tasks that you don’t already have to give a lot of cognitive effort to, like doing chores or going to the gym. (Eyal doesn’t restrict it so, however, so maybe you see it differently.) Just thinking that if I jump into learning more about my doctoral thesis topic, especially at this point when I should be wrapping the thesis up, all that extra learning would be a distraction, not adding traction.

What combines all the things learned in this module is that you never straight-up deny yourself from doing something, and you never straight-up do things against your will. Instead, you give your urges time to dissolve, or you reframe them, or you fool yourself a bit. I benefited the most from the approach of just sitting with the urge for a bit. It makes sense that it would help, as you’re probably looking for your phone or whatever your impulse is to get a moment’s pause from the effort of being focused on a task. Being focused can be a pain. A moment’s pause when you don’t actually think much was a great alternative to it.

This soft approach felt very different from full-on denying yourself from doing something, that something in my case often being getting a snack or switching to another task or, yes, sometimes looking at the phone. Especially switching to another task is what tends to derail my day. I think it’s called productive procrastination – you fool yourself into believing that you should do this chore or this email thingy-thingy or other so that you’ll then be able to focus on this big task better. It’s never good. It’s never easier to get back to it after cutting the stream of thought you were in. I used to get quite frustrated with this habit at the end of the day, realizing that I’d checked eleven boxes on my to-do list but not the most important one.

So, this is what I reflected on through the journaling prompt of day 6, “Describe one incidence when your mental abstinence backfired,” which was connected to the workbook exercise 5.

Just saying no to my urge to go fill the dishwasher or read the news app or just read this one more journal article to work on my 119th footnote for an hour to avoid working on the main text of my thesis still left the thought nagging in my head, persistently distracting my focus. During this 8-week experiment, I deliberately told myself no only to the act of saying a firm no.

My favorite of Eyal’s techniques was called “Leaves on a Stream,” one of the techniques I used together with the four-fold list. It’s simple: when you feel the internal trigger of discomfort rising within, you imagine that it is a leaf floating on a stream. You watch it go for a bit, twirling and circling in its place but eventually and unavoidably, at some point, floating away from you. I liked this exercise because of its aesthetics; instead of framing the urge as bad and stupid and unwanted, you frame it as something as innocent as a floating leaf.

Module III (days 9-13): Traction

The third module is about making time for focus, or traction, in your life. For Eyal, this means, first, defining what you want to spend your time on and then using the technique of time boxing to get that into your life. My time boxing habits in the week before this module looked like this:

Yeah, not like much. The poor sliver of a box is some automatic addition from my email, and it didn’t even relate to my life really. This module leads with the idea of discerning what you are distracted from instead of just focusing on being distracted. This really hit a nerve with me. I could go out of my way all day to fill obligations and yet feel unaccomplished. It’s not perfectionism; it’s lack of planning – I hadn’t put down what it was that I absolutely had to do and when.

In the video for day 9, Eyal vividly describes a normal day in the life of a person who reacts to other people’s plans rather than follows their own planning, a day filled with wanting to work on your well-being but your child needs you; trying to focus on an important proposal but your colleague needs you in a meeting; sitting in the meeting but browsing on your phone because you weren’t needed after all, etc., etc. Eyal sums up: “if you don’t plan your day, someone else will!”

The goal of this module is to learn this practice in order to be a person who plans and executes well. Eyal stresses that it is not the purpose to draw more time into your day from a magic well, but to understand that the time you have is already enough if you plan it well and commit to going through that plan. When your problem is the constant overwhelm of tasks and obligations, the problem you have is that you don’t give yourself the time to do what you say you will. This is at the core of the problem of being so overwhelmed that you, at the same time, end up overworking and underachieving.

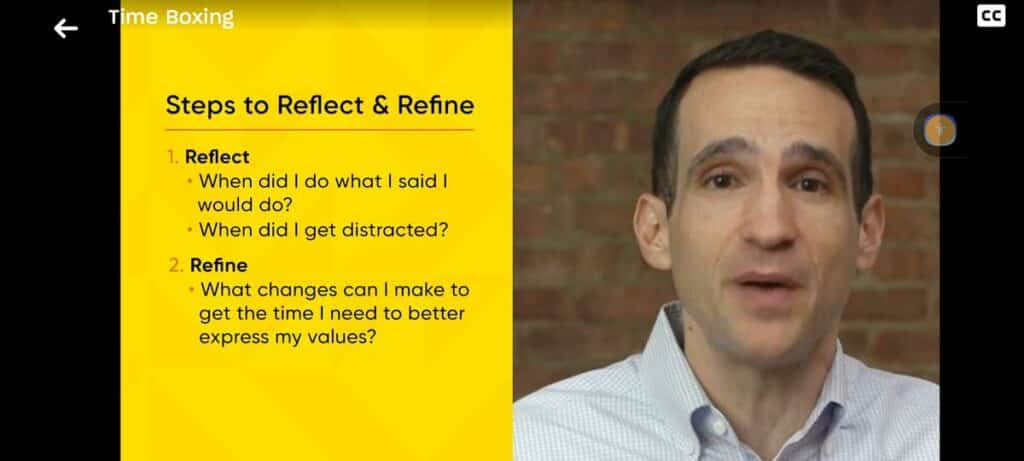

You don’t time-box to know what you’ll do, but to know why you should do anything. Citing a considerable number of psychological studies again, Eyal explains that time-boxing sets an implementation intention, an initial commitment that makes it a bit more likely that you’ll do what you say.

The boxes then again force you to realize that you can’t add tasks to your day endlessly. The boxes that end in your schedule are the results of negotiating your values and your rationale for what deserves your time.

This brings us back to the life domains that were mentioned at the beginning of this review. Eyal does indeed suggest that you’d benefit from time-boxing everything in your life – time for you, time for your relationship, and time for work. Maybe some of you find it difficult to at least at first see the difference between your domains of you and work. This tells us of the pervasive role that we’ve given to work. Maybe some of you find it ridiculous to start allocating time for work, as it allocates all your time for it anyway. All the more reason to become more aware of the time you knowingly allocate to it.

The workbook guides you through this. For all three domains of life, you’re asked to first name all the activities you’d want to do, then assess how much time they take, and finally put them down in your calendar. The life domains should be time-boxed in the order they’re given — first you, because you must function in order for the rest to happen, then relationships, because they are often the ones to give way to other commitments, and finally, work, in a conscious way.

These exercises were simple, but supported by the videos, they were pleasantly concrete in showing what needed to be done. Prior to this, my tactic for scheduling my day relied on a paper calendar and a to-do list for each day. I like the paper format of these things, but I must say that what I had on these lists was often over-ambitious.

Time-blocking takes time, more time than to just add one more task to the list. I didn’t fall in love with this habit right away, and I struggled to make it realistic for weeks. It took me about two hours per Sunday to make a draft of the week, and throughout the week I’d use a bit more time to make adjustments. However, I did master it towards the end of my experiment and have held onto it now, on my third week after the experiment, writing this. It took a lot of reflecting and revising, which, Eyal stresses, is an important part of learning and keeping up with the practice.

The key points to change in my schedule were to make use of the idle time of commuting, waking up earlier to write, and going to bed on time. This was a result of understanding how little time there is in the day. This is a cliché but it really, really taught me how to be more lenient with myself. There was no way I could finish all the things I’d previously put on my to-do lists. Toward the end of the experiment, I also got more things done. It was easier to finish things.

Weird side-effects of learning to commit to my plans were that I suddenly found time to put my hair nicely almost every day, focused more on my dental care routine, and quit drinking coffee. I don’t know why these happened, but they felt like natural extensions of this new version of me who has things planned out better. Anyway, I’ll share this week’s (week 18 of the year 2023) time block calendar at the end of this review to celebrate this win.

So, now Eyal has covered how to react to your distracting discomfort and how to plan time for doing what you want to do, and hold that time sacred. The next two modules focus on making your external situations match and work with your inner commitments.

Module IV (days 14-16): External triggers

This module acknowledges, in Eyal’s words, that “you can’t always meditate things away.” Sometimes the problems that stand in the way of focus aren’t internal. You might be highly motivated but get distracted by the things around you. I found this notion a relief. While distraction is a phenomenon beyond technology and the rings and the dings and the buzzes, technology undeniably contributes to the number of opportunities for distraction there is in a day. Technology is supposed to help you; now let’s make it help you.

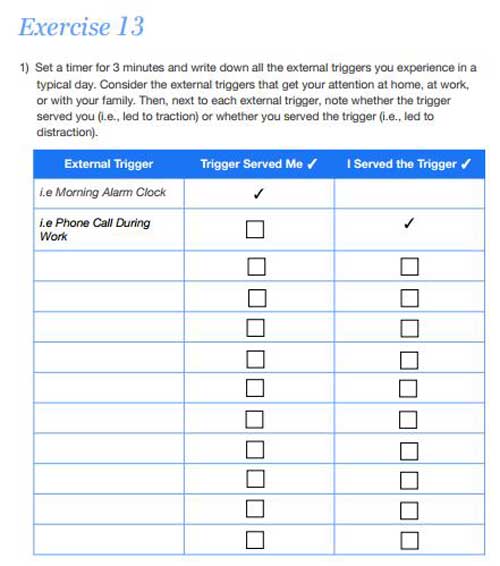

To keep engaging with a behavior, you need three things: motivation, ability, and trigger. Removing external triggers lowers your ability and, in the long term, your motivation to engage in distracting behaviors. Eyal explains in detail how to hack back your social media feeds, group chats, email, smartphone, online articles, desktop, meetings, and disrupting social contacts. What I offer here is a distilled version of the theory behind his tactic.

He calls this tactic hacking back our technology. He explains that studies show that it is not only stressful to be distracted by your phone when you cut your flow to look at it, but already knowing that you’d have a notification or a message but not responding to it right away causes stress. Moreover, simply seeing your phone on your desk is a cue for distraction, and it has been proven to be enough of a distraction to negatively affect your cognitive abilities. Negatively affect your cognitive abilities! That’s ridiculous, but when I tested it in real life, I could see it being true. You try it, too – it’s somewhat humiliating…

Hacking back is a kind of marikondoing of your surroundings. To start:

Really try completing this list. I guarantee it won’t include half the triggers you get! But you can always adjust later – the ones you can recall already probably make a long enough list. My list included: alarm clock, notifications from Trello, Whatsapp, Blinkist, Adblocker, OneDrive, Messenger, my daughter waking up in the middle of the night, my son not finding something in the fridge, me misplacing things and spending time looking for them, Outlook event reminders, call from a telemarketer, message from daycare, coworkers talking to me, strangers talking to me on the bus, call from a relative, email jamboree throughout the day. Three minutes done. Not all were negative. (For example, Eyal defines chatty co-workers as a distraction, but after five years of distance work, I embrace it).

I’ll focus on the smartphone here. There is nothing inherently bad in anything that your smartphone does. However, if, say, an app distracts you from spending time in your three domains in the way you’d like to, it is bad for you.

As said above, Eyal has sometimes disturbingly detailed techniques for hacking back the devices – action plans complete with specific lists of apps to download that take the decision-making away from you or that help you not to break your focus. Of these, I downloaded many but ended up only keeping using Forest (and already donated a tree, too).

The grand lines of hacking back your devices worked great. Go simple: The apps you don’t need, you remove. The ones you want to have but not at all times, you hide away from your home screen or desktop and instead put them into a separate folder that you have to deliberately navigate to. This removes the cue to tap them. You leave on your home screen only the ones that you need for your daily life and that make it more efficient—a navigation app, audiobook app, fitness app, alarm, calendar, etc. These make it easier for you to have cues only for the activities you want to commit to.

I adjusted my home screen into the above during the 8-week experiment and have kept it like that since. I love the calming look of it. In the small folders at the bottom, I have the apps that I need often but which do not make me lose time in them. (If you look carefully, you’ll see that Youtube is there, too. Sus. I have learned to use YT mainly as a non-visual podcast and mini course app, it’s education rather than entertainment, and I love it.)

Finally, you adjust the notification settings. Here, Eyal encourages you to be selective of which apps have the privilege of sending you notifications, and even within those, which of them can send audio notifications, which only buzzes, and during which hours. He admits that this might be very laborious to do at first. It is advisable to use the same categorization as you did when labeling apps as always allowed or restricted—maybe the restricted ones do not need to notify you of anything. I for one find it very difficult to know that my Candy Crush lives are full again, but I don’t get to play. Knowledge is pain!

These small adjustments need to be made only once, and they’re easy to do. I have found it immensely helpful not to get notifications of my news app, games, or social media during working hours. It’s not like you necessarily want to avoid working when engaging with these apps during working hours. Reading the news, for one, is generally considered a valuable way to spend your time. However, often I’ve just quickly glanced at what Prime Minister Sanna Marin has to say and found myself on the other side of the wormhole more than an hour later. It’s easier not to have that temptation but to actually allocate time to read the news, as it is really important for me to keep up with them.

The next module will show what to do when you still, after making all the adjustments so far introduced, struggle to muster the energy and headspace to stay consistent.

Module V (days 17-18): Pacts

Pacts can help you stay focused on your long-term goal. Therefore, pacts don’t target momentary distractions, but they nurture your will to stay consistent in your big goal—be that a fit and healthy body, a novel you want to write, finding more time for your family, or creating an online business. Pacts add friction to your slippery slope down the path to give up on consistency. In other words, it’s a precommitment that you make as the person who doesn’t want to give up.

There are three kinds of enforced promises you can make to yourself: Effort Pacts, Price Pacts, and Identity Pacts. I tried a version of each pact just for the sake of this review, but I would advise sticking to one. It felt a bit restrictive to have many, but as it was only for 8 weeks and not for life, I thought that I’d stick with it during this time.

Simply put, all pacts add resistance between you and the temptation to be inconsistent. The difference between the three kinds of pacts is where you place the resistance. This you choose based on what works best for you. I got some success with all of them, but will say that all of them also caused bursts of intense short-term stress. I’ll elaborate a bit on each.

Effort pacts make it more difficult to engage in unwanted habits by making it, one way or another, more difficult to engage in a behavior. My effort pack was quite classic, too: One of my vices, concerning my fitness goals, is to snack when I’m procrastinating, thus wrecking my calorie intake. I made the simple effort pact of not bringing any indulgent snacks to my house for the duration of these 8 weeks; if I’d want treats, I’d have to leave the house to buy them or bake them from scratch. There were two days when I still managed to snack unnecessarily by going through the trouble of making muffins out of the supplies I had at home, but all in all, it was a success, and I will keep up the habit of not having indulgent snacks available “just in case.”

Identity pacts make you break not just your actions but your integrity with the identity you want to hold. Think of the classic example of refusing a cigarette by not saying, “No thanks, I’m trying to quit,” but “No thanks, I’m not a smoker.” The identity pact that I made was a bit painful. Like all writers, I sometimes struggle to love my own writing and secretly believe, for example, that my doctoral thesis is unbelievably hideous. I decided to try believing – for the duration of these eight weeks – that I was a competent, definitely good enough doctoral candidate and researcher. This helped me to choose to participate in a 4-day writing workshop at my other university and consistently volunteer to share my work there for open criticism. After 8 weeks, even if I am slightly more confident with my writing, I cannot say that the faux identity stuck. I think it was too far-fetched, to be honest. Yet, it worked for that duration.

Finally, price pacts make you lose actual money if you don’t stick to your plan. You make the commitment to pay to another person. This is key; you need to be forced to pull through with the pact if you fail. Deeply uncomfortable, as Eyal admits.

A word of warning: Eyal explains that price pacts do not suit everyone. If you’re a person who simply cannot avoid external distractions, this is not the time for you to punish yourself for being derailed. Also, if you’re a person who likes to beat yourself up, this is not the style for you, either. You cannot build new behaviors without self-compassion.

The workbook very responsibly guided into creating price pacts –by first reflecting on the reasons for the distraction for pages on end (possibly to ensure that you don’t resort to a pact even though it’s really a matter of external triggers), and only after that, proposed that you’d make one:

My case was getting some writing done on a personal writing project I’ve been struggling to find time for. I wanted to complete one full chapter of that fictional novel during this 8-week period, and that would require me to chip in some words at least 15 minutes a day, six days a week, or 90 minutes per week. I made a pact that I would commit to doing that, and if I failed, I’d have to give that money to my kids to splurge on anything they wanted. Note: I didn’t make this pact known to my kids, but yes, to my spouse, who held me accountable for this. I believe that letting the kids know would have exponentially multiplied the number of external distractions in the house. So, if I don’t spend 90 minutes a week writing my novel, I will lose 200 euros. I’m happy to say that I completed not just the chapter I was working on but am halfway through the next, and my kids won’t, at least prompted by this experience, grow up to be slaves to capitalism.

This is it, all the four tools the course provides: mastering your internal triggers, minimizing your external triggers, making time for traction, and resorting to pacts as a last resort. The last two modules are basically celebrations of your effort to learn all you’ve learned during the first set of modules. Let’s put indistractability into practice with other people so that you can more easily keep your promises also to yourself.

Module VI (days 19-20): Workplace

This penultimate module addresses indistractibility in your work domain. Eyal encourages you to be open about your new habits but to understand that other people might not, at least honestly, and in the long run, be rooting for you. Making distractions visible and openly combatting them makes other people realize that they are not doing it. It would be more comfortable to see you fail. But you do you!

So, cue the indistractability worker entering the distraction-filled workplace. For most office workers, or people whose work otherwise involves a lot of emailing, controlling the email flow will already make a big difference. As the quest’s principles guide, you should not manically keep checking your email but allocate a specific time block for it. Eyal also suggests that when you send fewer emails, you get back fewer emails.

I tested this habit in my role as an in-house translator. I focused on the specific habit of asking for clarifications from clients before sending the translation. I would ask things like “in the third paragraph of this text, you refer to so-and-so as with this-and-this title, but to my best knowledge, they have been promoted to the role of this-and-this title. I will use that title rather than this title in the translation. Does this work for you?” This habit, however, forced me to adjust my work on that translation according to the schedule of the client’s response. Instead of doing this, then, I instead made all the corrections I deemed necessary already in the file I sent to them, and simply addressed them in the email. “I have updated the title of so-and-so from this to that title. If this edit was not necessary, please let me know, and I will send you a new version.” Most of the time, my corrections were on point, and the client thankful for the swift action. Success!

The other workplace habit Eyal suggests was to signal clearly to people that you’re indistractable – that during certain times you are not to be disturbed. He suggest printing out this sign (provided in the course, but as it is basically marketing material, I believe it’s fine to share it) and placing it in clear sight:

I did not do that, however, as it does conflict with my values in my workplace. I believe that it is worth it to lose your focus every now and then to hear about your colleague’s weekend or have them rant a bit about their life. We’re at the office not only to perform but to support each other to perform well. Therefore, I made use of the company’s flexible distance-work policy and worked from home during the days when I needed extra focus. I believe that when we’re at the office, we should, within reason, be open to helping others and use our working time to create a collegial company culture.

Instead of pushing people out of your sphere of attention, like suggested in the quest, it might thus be better to share what you’ve learned on the quest, even if your colleagues would, at least at first, be only superficially interested and deep inside annoyed. You are not the only one struggling with distractions, but you may be the only one, in your workplace, with a practical solution.

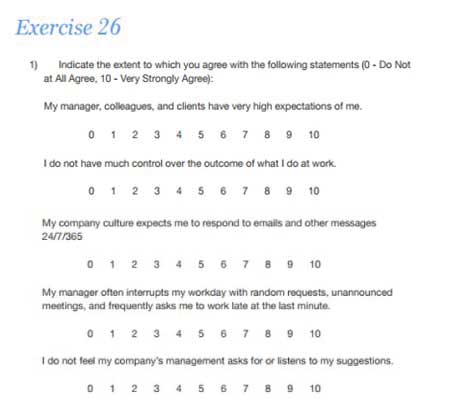

Some workplaces are stuck with their toxic culture of perpetual distraction. The exercise book’s exercise 26 helps you identify how toxic your company culture is. By circling the value on each of these scales, you get a number. The higher, the more dysfunctional your workplace:

As you see, the exercise book helps you identify the problems and, beyond the above exercise, also the ways in which you and your colleagues shoot yourselves in the foot by distracting yourselves from impossible working conditions. My position in my working place is quite special in the way that I am building a new role inside the organization, thus being able to dictate very much of what I do, and at the same time, my role doesn’t require daily reporting to anyone but myself. However, I can see very easily how these questions are ones that one should keep in mind.

While this is valuable knowledge, I believe that after taking this course, you also do have the tools to suggest solutions to those problems. You have the tools to identify the sources of distractions and the patterns that lead to people being overworked yet underachieving. You have the right words for describing these phenomena. Maybe the people in your workplace won’t be open to your suggestions, but maybe they will!

Let’s hope the people close to you are, at least. That is the topic of the last module.

Module VII (days 21-27): Relationships

This final module addresses indistractibility in your relationship domain. In a series of very short, practical videos, Eyal explains how to build romantic relationships unhindered by digital gadgets, friendships between adults unhindered by children, and a parenting relationship with your children unhindered by your own distractions.

The gist in all of these types of relationships is to devote time to that relationship and commit to that time. This is not too difficult, right? And yet we know it is. Eyal tells a set of painfully relatable stories about checking one’s devices when with a friend, child, or spouse and sending the message that whatever is on the phone is more important than the person in front of you. You don’t mean to say that you don’t care about them, you do care about them, but you also end up showing that you don’t.

Then he gives a clear action plan for fixing this.

First, become an indistractable friend. In adulthood, spontaneous hanging out with friends happens very rarely, even though most people would love to have that element, typical of childhood friendships, when you just exist with your friends and talk about nothing. Yet, we need that in order to have truly fulfilling friendships.

Attempts at spending time together are rarely distraction-free. Do you find yourself phubbing around your friends? If you don’t, it is likely that you are an exception. Eyal suggests that it’s time we’d make phubbing as unwanted behavior as smoking once was by spreading social antibodies.

Due to the social antibodies around smoking, you non longer assume that your friend would be ok with you smoking in their living room or that you could light up on a plane. Yet, he points out, it was only a few decades ago when that was totally acceptable. Attitudes around smoking changed quickly after we learned the harmful effects of it. The same can happen with phubbing, so find ways to discourage phone use.

It’s a bit awkward to do that. After all, you’re sort of correcting people, and that, of course, comes across as a bit condescending. I tried this with a friend who, a bit tired, I guess, forgot herself in a scrolling session when just checking what so-and-so wrote on Whatsapp. Using Eyal’s example phrase “Oh, I see you’re on your phone. Is everything ok?” I was very self-aware of making a statement rather than really asking anything. She just laughed a bit and said, “Yeah,” and put her phone away. No harm done!

Then, become an indistractable lover. Yes, lover, even if it’s your wife/husband of decades. (Obviously, especially if you’ve fallen far away from each other, becoming lovers again requires that you both see the problem and that you’re both willing to do something about it. Here, we assume that you do at the point you decide to try becoming indistractable in your relationship.)

Indistractable lovers are, simply, indistractable in each other’s company on the time they’ve allocated for that. A simple way to make that time distraction-free from children is to devote the late hours of the day, after the kids are in their own beds already, to screen-free couple’s time. This is where it often (also in Eyal’s own life in the past, as he explains in a relatable anecdote) goes astray. At the end of the day, everyone is tired, of course. It’s tempting to just swipe away on your screen or, maybe, work a bit still in the hopes of that bit of extra work creating more space on your following working day. Instead:

All of these are tactics learned on the quest. Understand that committing to screen-free time can cause discomfort, and use what you’ve learned in module 2 to cope with that together (e.g., sit with it for a bit).

Commit to setting a specific time in the day to make time for traction – attraction – to exist between you and your partner with what you’ve learned in module 3 (e.g., time-block a screen-free couple’s time for each night). Remove external triggers from what you’ve learned in module 4 (e.g., set a timer on your router, use smart notification settings). And finally, use pacts to make sure that even on the days when you’re more tempted than usual, something makes it more difficult to stick to your pre-commitment by using what you learned in module 5 (e.g., by increasing the effort for turning on your router by placing it uncomfortably).

I believe it’s a common tale that people with children go on a holiday with just the two of them and are reminded how much fun they used to have together. Makes sense, doesn’t it? On holiday together, you would share experiences and not isolate yourself in your work or chores. Eyal points out that we play so many roles that slipping away from your role as a loving partner doesn’t need to mean that there’s anything wrong with your relationship. My relationship is still quite young, and the will to devote time to each other comes naturally. Testing this part of the quest, for me, meant paying attention to the habits we have to avoid distraction and marking them as something to hold on to and encourage.

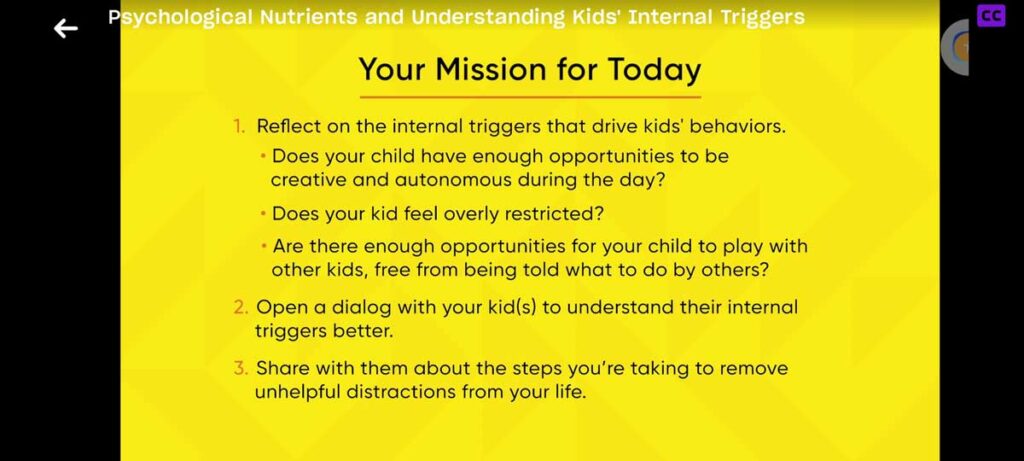

When it comes to children, Eyal calls out parents’ tendency to blame outside excuses for their child’s unwanted behavior (guilty as charged!) Like sugar highs, too much screen time is often pointed to as the reason for a kid being out of control. Restricting screen time straight-out didn’t work for adults – why would it work for kids? Eyal encourages parents to teach their children what they have learned during the quest so that the kids can become more aware of how they use screen time, not simply how much they use the screen. There are good things that screen time teaches; it meets some real needs.

Eyal points out that playing a game, for example, can make your child feel competent, and the time spent playing with online friends can meet the need for relatedness – forming meaningful connections with others. Obviously, when their screen time starts to hinder their schoolwork or other social life, someone needs to restrict it. However, that should, according to Eyal, be your child, not you.

Instead of setting boundaries, he encourages taking the longer route and discussing the effects of the choices your child makes. After reflecting on the importance of, say, studying, ask your child whether failing on a test is a reasonable price for playing and not studying? What do they want to achieve, for instance, during this school year, in their studies or hobbies? Draw the connections between actions and consequences clearly, and really have them make their own schedules (age-appropriately), even if they wouldn’t match your idea of a good schedule. It is an invaluable lesson.

The parents’ job, then, is not to make the rules but to ensure that the kids keep the commitments they made to themselves. You should help them understand their internal triggers and manage them, to control their external triggers, teach them to keep a calendar, and make pacts when something is extra challenging but also important. This shifts your role as a parent greatly, and it might be awkward at times. But imagine if you really succeed in teaching your child what you’ve learned on this quest—what an asset that would be for them in life.

Final results – the situation on the first and last day

The quest doesn’t really have a summarizing video – it just ends, a bit abruptly, after the content on child-raising, with a brief farewell underneath the last video:

A sense of conclusion is, however, achieved by returning to the survey that was also filled in on the first day of the program (see the beginning of this review). Back then, I got 11/64 points (0-6 on the following scale):

Let’s revisit it! So, after coming to the of the quest, the survey asked the same eight questions (and I now answered):

1. My schedule reflects my values, aspirations, and goals. I rarely go off track

Agree (5). Time-boxing really makes it possible to understand that you can’t fill each of your days with all your goals. Much of my feeling of being off-track was caused by unrealistic expectations, and this little fix in my planning routine has helped me incredibly.

2. I can stay focused on achieving my goals and living a purposeful life. I am fully in control of how I spend my time.

Somewhat agree (4). I still have a lot of moving particles in my life, and cannot predict how the combination of them plays out. However, even when the circumstances change, I usually have a clear idea of what is important to do that day, and I have more skills now to understand that really focusing on that, instead of checking eleven less important boxes, should take precedence.

3. I know how to master cues in an external environment that lead me to distraction.

Agree (5). Yes – now I know what this means, first of all, and I am fairly good at controlling external distractions, mostly because those measures require very little effort after they’ve become a habit.

4. I know how to use my e-mail, group chats, desktop, smartphone in a way that stimulates my efficiency and productivity.

Agree (5). I do! My email habits were never a huge issue, but now I’ve mastered them even better, I love my calm home screen, and due to the way it’s organized, I’ve listened to more podcasts and books and used focus-enhancing apps to increase my productivity.

5. I’m fully present in the now absolute majority of the time.

Somewhat disagree (2). I still live in the future, even though it doesn’t hinder my performance as much as before. I think this is part of a larger issue for me.

6. I easily avoid being distracted by technology.

Agree (5). Yes, it is not too distracting for now. I allocate time for just scrolling away and rarely find myself doing it at other times.

7. I am deeply aware of my internal triggers, the root causes of my distractions, and I know how to navigate them.

Strongly agree (6). This increased understanding of my internal reasons for getting distracted was, alongside the technique of time-boxing, the biggest change for me. It helped me be kind to myself and just easier to work with myself.

8. I have strong routines that help improve my productivity.

Agree (5). I had pretty good routines already before this, but now I’m more consistent and more realistic with those routines.

Look at that: 37/48! Not bad development from just 11 at the beginning. It was useful to also compare concretely the starting and ending points. Eight weeks isn’t a lifetime, but it is still long enough time for progress to happen slowly enough to go undetected if not making a structured effort. Now, my final thoughts on this quest!

Final thoughts

As I went in with an ambition to review the course comprehensively, the picture portrayed in this article about the course is probably a bit fuller than it would be in practice for you. You, most likely, would benefit the most from restricting it a bit, focusing on the areas that contribute the most to your distractions. At the same time, the exercises and journaling prompts, and the content I described in this (admittedly hefty) review still covered less than a third of the quest’s exercises and more fine-tuned techniques and tweaks to them.

The opportunities to improve your life through this quest are greater than I’ve been able to express in this review. It is indeed a rich source of inspiration for falling in love with your own life as a counterforce of falling to the constant distractions from it. This quest is simple, efficient, and practical. I have benefited from it during the eight weeks (and beyond them, as now I’m actually on the third week after the test period), and I do recommend this to all who want to hack their brain back instead of imposing repetitious and forced screen-time restrictions in hopes of suffocating the need to engage in another doom-scrolling session.

PS – this is my time-block calendar for the ongoing week’s working hours. I’ve learned to devote time for writing every morning before the kids wake up, do a bit of work in the morning at the home office to be able to end the day earlier, I’ve learned to make use of my commuting time, and have a good block in the middle of each day for my actual payroll jobs instead of them creeping into all the others. I think I’m starting to get the hang of this thing called being crazy optimized!

Need more information?

If you are intrigued by this quest but want to learn more (even though this review should provide you with a pretty good idea!), your first stop should be its information page at Mindvalley. If you’re able to see beyond the pretty high-octane marketing material, you’ll find some more details there.

There is also a masterclass offered by Nir Eyal, an hour-long session, which basically serves as a teaser for the full course.

Accessing the course

Becoming Focused and Indistractable is accessible through the Mindvalley Membership, which gives you access to all quests and learning communities on the platform. The cost for membership is $99 per month or $499 if paying for a year upfront (for a monthly cost of $41.60).

Membership comes with a no-questions-asked trial period of 15 days. With a suggested pace of a lesson a day, this gives you plenty of time to test out the quest (and any others that you might be interested in) and cancel if you don’t feel this is for you.

Black Friday Special – get 40% off your Mindvalley Membership to get access to 100+ personal growth programs. Note that the discount is applied to the lifetime of your account – not just your first payment.